belied (14): misrepresented.

with false compare (14): i.e., by unbelievable, ridiculous comparisons.

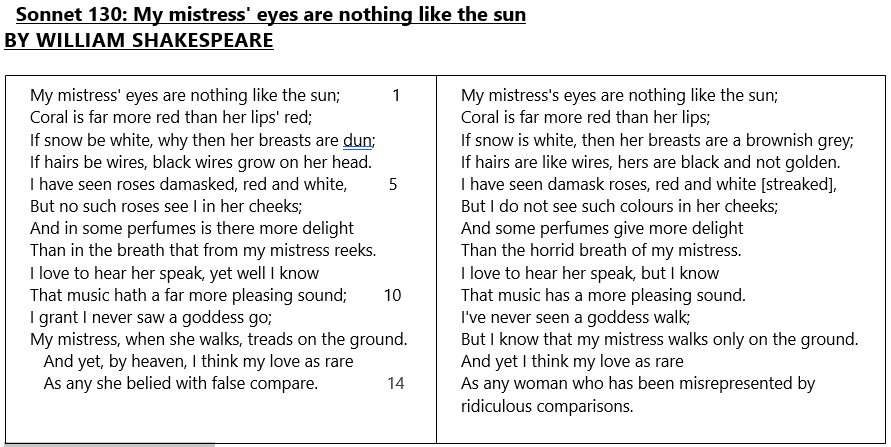

Sonnet 130 is the poet’s pragmatic tribute to his uncomely mistress, commonly referred to as the dark lady because of her dun complexion. Sonnet 130 is clearly a parody of the conventional love sonnet, made popular by Petrarch.

In many poems the poet’s lover is as beautiful and, at times, more beautiful than the finest pearls, diamonds, rubies, and silk. In Sonnet 130, the references to such objects of perfection are indeed present, but they are there to illustrate that his lover is not as beautiful. Shakespeare ends the sonnet by proclaiming his love for his mistress despite her lack of beauty.

One final note: To Elizabethan readers, Shakespeare’s comparison of hair to ‘wires’ would refer to the finely-spun gold threads woven into fancy hair nets. Many poets of the time used this term as a benchmark of beauty.

Commentary

This sonnet, one of Shakespeare’s most famous, plays an elaborate joke on the conventions of love poetry common to Shakespeare’s day, and even today. Most sonnet sequences in Elizabethan England were modeled after that of Petrarch. Petrarch’s famous sonnet sequence was written as a series of love poems to an idealized and idolized mistress named Laura. In the sonnets, Petrarch praises her beauty, her worth, and her perfection using an extraordinary variety of metaphors based largely on natural beauties. In Shakespeare’s day, these metaphors had already become cliché. The result was that poems tended to make highly idealizing comparisons between nature and the poets’ lover that were, if taken literally, completely ridiculous. My mistress’ eyes are like the sun; her lips are red as coral; her cheeks are like roses, her breasts are white as snow, her voice is like music, she is a goddess.

Sonnet 130 mocks typical metaphors by presenting a speaker who seems to take them at face value, and somewhat bemusedly, decides to tell the truth. Your mistress’ eyes are like the sun? That’s strange—my mistress’ eyes aren’t at all like the sun. Your mistress’ breath smells like perfume? My mistress’ breath reeks compared to perfume. In the couplet, then, the speaker shows his full intent, which is to insist that love does not need these conceits in order to be real; and women do not need to look like flowers or the sun in order to be beautiful.

The rhetorical structure of Sonnet 130 is important to its effect. In the first quatrain, the speaker spends one line on each comparison between his mistress and something else (the sun, coral, snow, and wires. In the second and third quatrains, he expands the descriptions to occupy two lines each, so that roses/cheeks, perfume/breath, music/voice, and goddess/mistress each receive a pair of unrhymed lines. This creates the effect of an expanding and developing argument, and neatly prevents the poem—which does, after all, rely on a single kind of joke for its first twelve lines—from becoming stagnant.

Sonnet:

From the Italian for “little song,” a poem usually rhymed, 14 lines long, and in iambic pentameter

Elizabethan or Shakespearean Sonnet

This sonnet has a form in which the rhyme scheme is abab,cdcd,efef,gg. This is an adaptation of the Italian sonnet with a “summing up” couplet at the end.

Petrarchan or Italian Sonnet

This sonnet’s form has a rhyme scheme which divides the poem’s 14 lines into two parts, an octet (first eight lines) and a sestet (last six lines). The rhyme scheme for the octet is typically abbaabba. There are a few possibilities for the sestet, including cdecde, cdcdcd, and cdcdee.

Iambic Pentameter

A meter in which there are five iambs (pairs of unstressed and stressed syllables) in each line. An iamb is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one.

O. K., so much for the fancy language. Basically, in a sonnet, you show two related but differing things to the reader in order to communicate something about them. Each of the three major types of sonnets accomplishes this in a somewhat different way.

The point here is that the poem is divided into two sections by the two differing rhyme groups. A change from one rhyme group to another signifies a change in subject matter. This change occurs at the beginning of L9 in the Italian sonnet and is called the volta, or “turn”; the turn is an essential element of the sonnet form.

Questions:

- Name and explain two things to which the poet compares his mistress.

- Outline 2 features of a Shakespearean sonnet that you can identify.

- How does Shakespeare’s poem differ from traditional love poems?

- Identify and explain the volta in the poem.

- Discuss whether you think the speaker’s love is sincere.